Texture and Timbre: Photography and Sound in Halfway to White

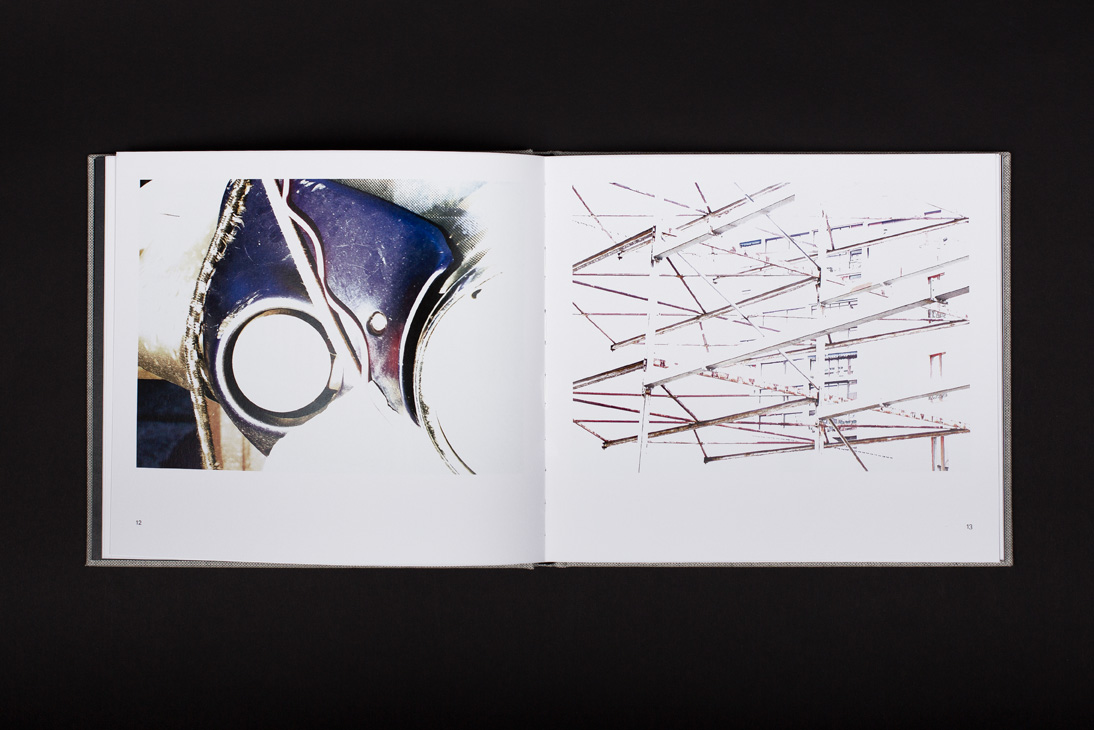

Halfway to White book spread. Image courtesy Joséphine Michel

Joséphine Michel is a French Photographer, who has recently collaborated with the Finnish electroacoustic composer Mika Vainio to produce the book and audio CD, Halfway to White.As John Cage would have it, the spaces between the notes are equally as important as the notes themselves in creating the sonic texture of a piece of music. In Joséphine Michel’s photographs many of the recognisable, or one might say figurative, details are virtually bleached out, remaining only as pallid traces and, as a result, many of the details that were formerly incidental or peripheral, take on a new, albeit abstract, significance. In these images, as newly empowered voids realign with the surrounding forms, reality becomes re-invented. The ephemeral has, in effect, been elevated, creating a new set of parameters for our visual perception of those scenes. Through the sampling, processing and filtering of everyday sounds Mika Vainio likewise offers us aural experiences that sit outside those soundscapes that are part of our everyday world. Together Michel and Vainio challenge our often-jaded perceptual habits and patterns, offering a whole new palette of experiences, both visual and aural.

Freelance art critic and curator Roy Exley interviewed Joséphine Michel about her recent work.

Roy Exley: In your recent project leading to the publication of Halfway to White, how closely did you collaborate with Mika Vainio, did the visual inspire the aural, or vice-versa, or was the dialogue more symbiotic than that? What inspired your collaboration with Mika, had you worked with him previously?

Joséphine Michel: It is a circular process. I was listening continuously to Black Telephone of Matter and Heijastuva (which means ‘light reflected’ in Finnish) when I started making the first images of Halfway to White, which began as an exclusively photographic series. Jon Wozencroft (the co-director of Touch, who published the book) chose one of my photographs for the cover of Fe 3O4 – Magnetite, knowing I was a keen admirer of his work. Having heard through the grapevine that Vainio liked the cover, I wrote to him saying I would be delighted to nurture further collaborations with him. He proposed to create five pieces of music for Halfway to White. So his music inspired my photographs in the first place, which led, as in a loop, to the creation of music.

RE: Have you considered exhibiting your work in a gallery context where viewers would be encouraged to listen to Mika’s, may I call them ‘sound pictures’, to compliment the viewing of your work?

JM: Last year, in 2014, I was invited by Jorge Villacorta to show Halfway to White at Wu Galeria in Peru, during the Biennale de Fotografia de Lima. Mika Vainio had just composed his pieces, which, he himself admits, were intense and could be extremely abrasive for the persons working in the gallery. We decided in the first instance not to install them. However, after an evening of public presentation where we let the music flow in the rooms, we realised how the viewer/listener’s experience was heightened. In this immersive photographic and musical installation, the degree and the quality of attention towards the photographs were different. Vainio’s music, instead of distracting people from the photographs, intensified their experience, creating a sort of ‘vibratory static’. We therefore decided to let the music remain for the rest of the exhibition. Potential exhibitions are arising – and yes, the music will be experienced alongside the photographs.

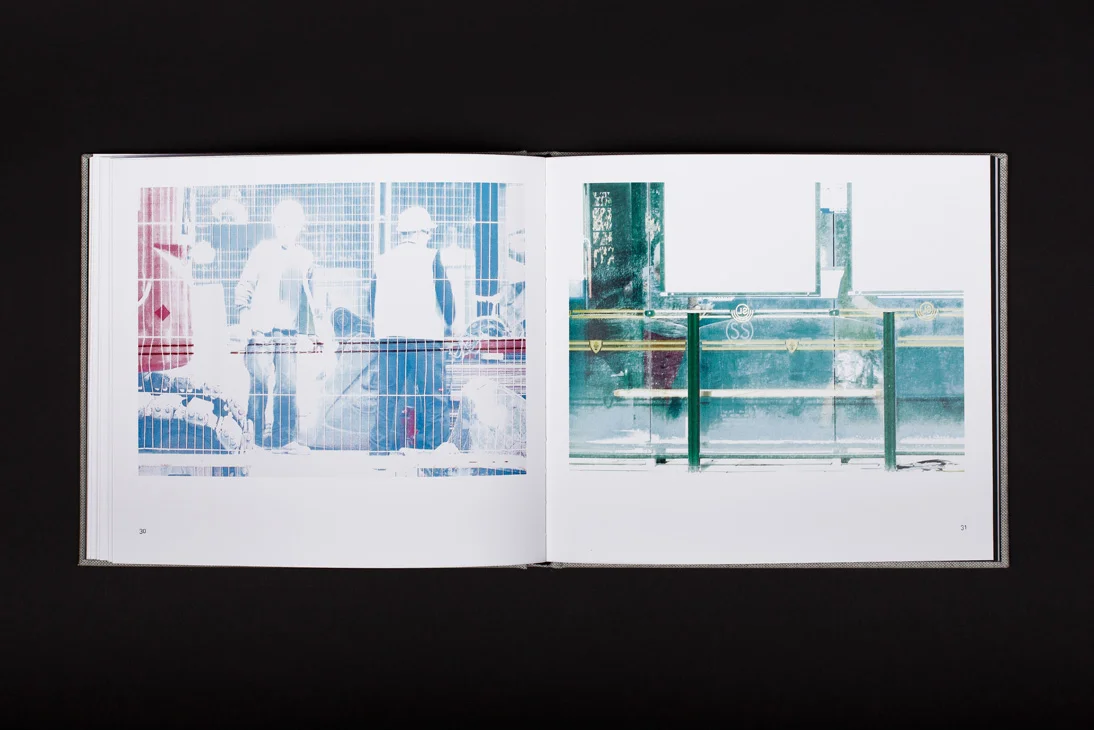

Halfway to White book spread. Image courtesy Joséphine Michel

RE: I don’t know whether re-configuring or de-configuring is the right word to describe how you process and manipulate your images, but what interests me is whether this is a progressive process, where you move gradually, through a sequence of adjustments to the image that feels right?

JM: My photographs derive from straight photography: they are the way they are by simple adjustment of the exposures at the moment of shooting. I don’t process them, and employ a minimal use of post-production. I use a digital camcorder to create my images, which affects the quality of the overexposure, allowing certain colours and contrasts to resist, whereas when you overexpose with a photographic camera, every part of the image tends to fade. There is no pre-meditation in my method of working, just an improvised, visual reaction to a noise field. I never know beforehand what I am going to photograph, nor, as in the case of Halfway to White, the amount of overexposure I am going to use. There’s a multiplicity of whites in Halfway to White, tones being in concordance or contrasting – they are basically variations around what was initially an accident, the excess of light in the image.

RE: Does the amount of visual obfuscation that you employ vary with the pictorial content of an image, for instance if it is an archetypal, instantly recognisable scene, would you use more obfuscation and, perhaps, less, where the scene is more peripheral and ambivalent?

JM: Ambiguity is important – I am interested in what comes to light when the representational facet of a photograph approaches erasure. My criteria for the lightening of the image is based on an intuitive response to the way aspects of the image recede or advance, to create a new conjunction of forms or significances. It’s interesting that you speak about obfuscation when it comes to overexposure, which is, strictly, a lightening of the images. This is a less normative and value-laden way of speaking about them.

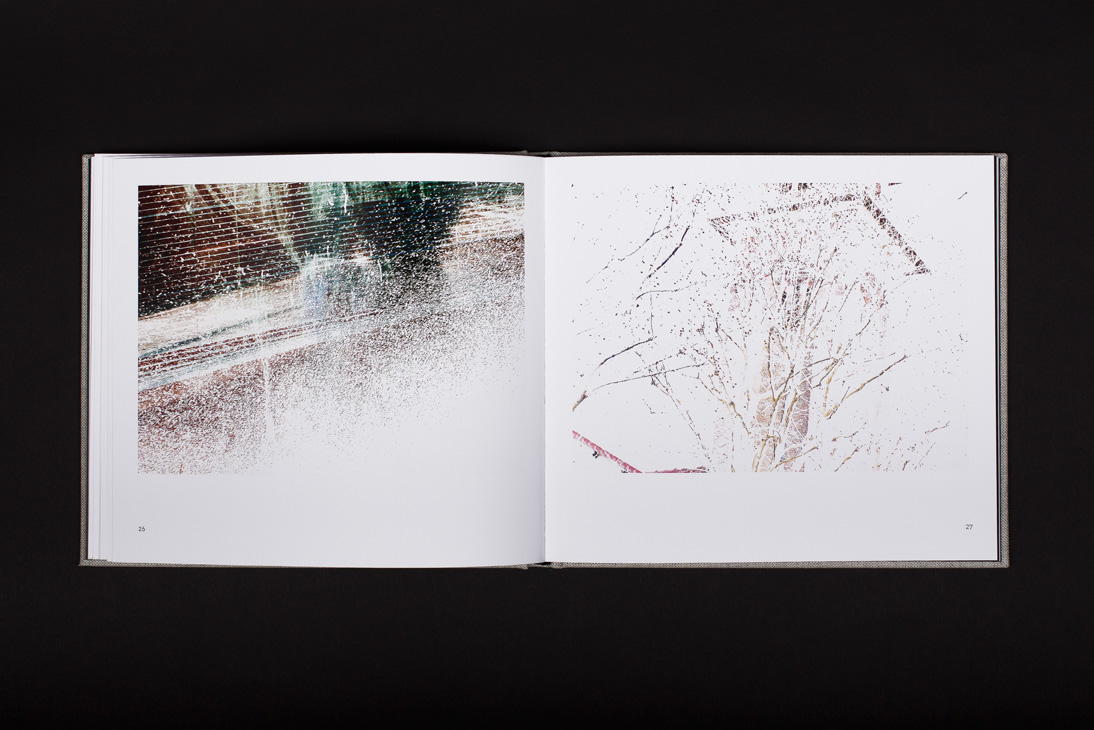

Halfway to White book spread. Image courtesy Joséphine Michel

RE: The visual threshold between abstraction and figuration in an image can be extremely fine and ill-defined, endlessly mutable, does this challenge, the principle of uncertainty, attract you to this mode of working? If that is not the case, then what is the main motivating force that drives your work forward?

JM: Perhaps more than the threshold between abstraction and figuration, the energetic tension between concreteness and abstraction is one of the central issues at stake in my work. Some things might not be figurative, but are nonetheless concrete. I was very interested in what could be called ‘pre-sounds’ or ‘quasi-sounds’ in Vainio’s music – some micro-sounds, close to silence, which you feel are concrete without being able to source them.

Reciprocally, where photographic abstraction is typically an effect of framing, I settle abstraction within the framing, rather than by it. In Halfway to White, the framings might be sometimes frontal and rectilinear, but the lightening renders the image abstract by stripping the forms of their spatial position or orientation, so that, for example, forms on different planes interact or combine in disorientating ways.

RE: How do you perceive the correlation between the wide-ranging textural timbres of Mika’s sonic world and the intricate pictorial textures in your images – is this principally about textures, a sculptural bridging of the aural and the visual so to speak, or is this phenomenon merely one aspect of your collaborative work?

JM: Textures, for sure, are crucial to the relationship between Mika Vainio’s music and my photographs. I have also been deeply attracted by the way Mika conveys a multiplicity of moods, from violent to delicate, in a very minimal but moving way. I like the notion that moods could be textural: it implies a ‘sculptural bridge’ as you call it, between something mental and something material that echoes the terms suggesting correspondences between the sonic and the visual; reverberation, tone, etc. in an interconnected sensorium.

This interview was published by The Photographers' Gallery in MARCH 2015

Halfway to White is available for preorder through Touch.

Joséphine Michel is a photographic artist born in Paris and currently living in London. She studied philosophy at the Université Paris-Sorbonne and photography at the École Nationale Supérieure de la Photographie in Arles. She subsequently undertook a research project (MPhil), titled ‘The Sonic Photograph’ at the Royal College of Art. Her work focuses on the impact of sound on photography, in terms of reverberation, texture, tonality and interferences. She published her first book Lude, Filigranes Editions, in 2007; her second book, Halfway to White, in collaboration with the musician Mika Vainio, is published by Touch.

Roy Exley is a freelance art critic and curator. He has written for many art magazines and journals and is currently a regular contributor to the contemporary photography web magazine Photomonitor. He has curated eleven exhibitions of contemporary art in London and Paris since 2000.